This post was originally published on this site

MarketWatch photo illustration/iStockphoto

Even as Wall Street declares a contested presidential election as one of the biggest risks to the stock market rally, some are quietly looking at betting that swings in U.S. equities around election time won’t be as violent as feared.

A large camp of investors fret that the intense acrimony between the Democrats and Republicans, a fight over who will decide the next Supreme Court justice, and doubts about the ability of Washington to reach agreement on another round of aid to the economy could create a perfect bearish storm for a stock market that traded at records only a few weeks ago.

Yet for some, the heightened interest in hedging against volatility through the derivatives market is enticing some to take the other side of the trade, in effect, wagering against equity turmoil.

Clifton Hill, global macro portfolio manager for Acadian Asset Management, said volatility looked “expensive” and added his firm is among those assessing whether to place a short position against stock-market turbulence.

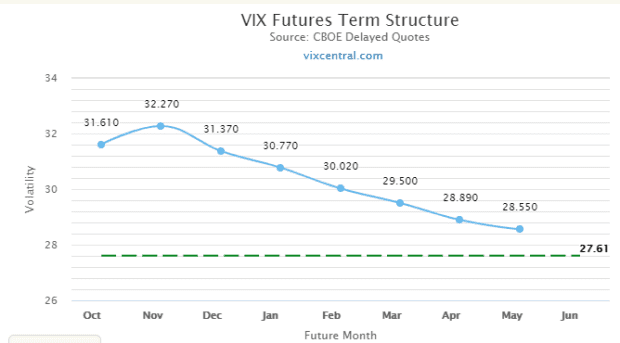

Fears of heightened volatility have lifted prices for November futures contracts tied to the Cboe Volatility Index or the VIX VIX, which measures expected volatility over the coming 30 days for the S&P 500 SPX. Buying these futures offers insurance against any rise in volatility.

The VIX was at 26.73 on Monday. A VIX future expiring on November 18, which would encompass the presidential election period, was trading at 32.90, according to data from Cboe.

Volatility has tended to fall much faster in previous elections

vixcentral.com

“There’s a broad consensus that November is going to be very volatile. Me and almost every one thinks November is going to be a contested election. Hedging against some of that makes sense,” said Max Gokhman, head of asset allocation at Pacific Life Fund Advisors, in an interview.

But unusually, prices for volatility futures for December and January are elevated, too.

“It’s a bit unusual. Normally, you would have implied volatility rising ahead of the election and then dropping off,” Marvin Loh, senior global macro strategist at State Street, told MarketWatch.

See: Ahead of the U.S. election, here’s how top fund managers see the market risks and opportunities

That’s what some of the volatility bears say is still likely to happen.

Such market participants argue that they still expect the market to show bigger swings around the election, but that pricing for VIX futures and other volatility gauges had run so high that they were now trading at a “premium.” In other words, they had more than baked in any market turbulence that was likely to result during and after the presidential election.

So how do investors bet against volatility?

Market participants could either do this by selling VIX futures or put options, which gives holders of the option the right, but not the obligation, to sell the underlying asset at a specific price by a certain date.

By taking the other side, a seller of the put option would be required to buy the asset if they drop to a certain level yet in return would earn a steady income if the option is not exercised.

“The elevated premium provides an interesting opportunity to accrue insurance income in a world starved of decent yields,” said Van Le, a portfolio manager at GMO, in a note.

Yet ultimately, the perception of whether volatility was cheap or expensive ultimately depends on who you are, according to Hill.

For money managers looking to protect their portfolios against a sharp drawdown in the S&P 500, any options that become worthless due to the election not triggering an intense bout of volatility should be considered as the cost of insurance.

But for more specialist managers who frequently trade volatility derivatives, the current pricing might look more attractive.

This elevated cost to insure against volatility could therefore reflect how “there are a lot of true hedgers as opposed to speculators,” said Gokhman.

This article was originally published on September 22.