This post was originally published on this site

As pent-up consumer demand for used and new vehicles meets a pandemic-fueled parts shortages, auto makers are changing the way they do business and one style of car is even getting an unexpected boost.

Add cars to the growing list of items that are pricier and harder to get, with no change in sight at least for this year: Vehicles are staying on lots for far fewer days, sales incentives have dried up, and auto makers are missing out on sales because their inventories are so low.

May’s seasonally adjusted annual rate of about 17 million cars sold in the U.S. was down from about 19 million in April due to the tighter inventories, but up from 12 million in May 2020, one of the worst months in the U.S. in terms of COVID-19-related shutdowns and restrictions.

If not for tight inventories, however, observers say that May’s seasonally adjusted annual rate would be closer to 20 million.

“You wouldn’t see pricing as high as it is if there wasn’t a backlog of demand that is not being met,” said analyst Karl Brauer with iSeeCars.com. “There’s absolutely potential for more sales … Production is not keeping up with the level of demand for new cars.”

May sales were better than expected and “quite strong all things considered,” but it’s clear that the market is starting to see the impact of the supply situation on end demand, RBC Capital analyst Joseph Spak said in a recent note.

“Inventory constraints (are) beginning to show up in sales results,” he said.

This was most evident for Ford Motor Co.

F,

Spak said, which has lost out on sales of its best-selling F-150, with F-150 inventories already low coming into the ongoing chip shortage because of a model changeover.

See also: GM stock ends at record after auto maker says first half will be ‘significantly better’

“We wouldn’t be surprised to see the impact begin to creep into the results of other OEMs over the coming months as we don’t think inventory is likely to begin to improve until late summer and potentially not normalize until 2023-24 time frame,” Spak said.

The seasonally adjusted annual rate could drop in the coming months on a continuation of a supply-driven slowdown amid demand that “remains quite healthy,” he said.

General Motors Co.

GM,

earlier this week said it was starting to build SUVs and pickups without a common fuel-economy feature, its automatic stop and start system, because of the chip shortage.

Several auto makers got creative, spreading out the chips they had, leaving out chips in easy-access areas in the vehicles and then storing the nearly finished cars until they got a new batch of needed materials. Tesla Inc.

TSLA,

Chief Executive Elon Musk tweeted recently that Tesla prices were increasing due to the supply-chain pressures.

The pandemic brewed both the surge in demand and the shortages.

Cooped up in their homes amid public-health shutdown orders, and newly wary of public transportation, taxis, and ride-hailing, a lot of people realized they wanted a car, iSeeCars.com’s Brauer said.

Related: Ford stock jumps as plan to offer more electric vehicles earns Wall Street praise

That was the initial catalyst for sales, exacerbated by the ability for some to work remotely, which sent some workers away from urban areas and more dependent on cars.

Then came the chip shortage, made worse by work-from-home and remote school becoming common place in many areas, and new gaming consoles coming to the market, all using chips that only a handful of companies make.

Besides chips, the pandemic also disrupted other supply chains and the auto makers’ raw-materials pipeline. Some auto companies had better supply connections or had hoarded supplies more than others.

The new constraints will lead to a “massive re-examination of the supply chain system,” Brauer said.

For a long time, there was a respect and admiration for a “lean” style of management, he said. In more plentiful times, a just-in-time production seemed like a brilliant cost saving measure.

“Then all of sudden lean production meant no production,” he said.

Companies will have to re-evaluate how they’ll run themselves in the future, whether they’ll rely on one supplier for a need or several, even if it costs more to keep those lines alive.

Tight inventories are unlikely to shift before 2022. It will take a while for chip makers to get get up to speed and auto makers to reassess supply chains, Brauer said.

We are likely to hear more about the ways the companies are trying to sidestep the shortages and the near-term future of supply and inventories when auto makers report second-quarter earnings in July and after.

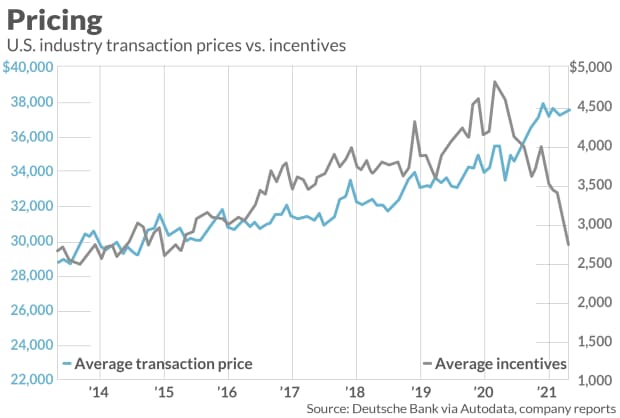

A recent note by analysts at Deutsche Bank said that in the industry average retail transaction pricing has continued to trend higher, and auto makers’ incentives all but dried up.

Vehicles are also spending fewer days on lots, with the industry as a whole looking at 23 days on market, about 10 days fewer than in April, and 38 fewer days from May 2020. By auto maker, analysts put Ford’s supply at 30 days, Stellantis NV

STLA,

at 28 days, and GM with just a 22 days’ supply.

For consumers, it will not be just a matter of paying more for a car. It will be about being flexible about which car to buy, and willingness to go farther than they may have wanted to get their choice.

Used pickup trucks have been perennial hot buys and even more so with the pandemic, Brauer said.

Interestingly, however, the No. 2 spot among hot used cars doesn’t belong to used SUVs.

Although that body style continues to be popular, the next leading auto segment in recent months has been convertibles and sports cars, Brauer said.

“It is the two opposites,” he said. Trucks are perhaps the most utilitarian vehicle one can buy, and coupes are the least practical, he said. Used trucks and convertibles have gone up in price around 25% and are the least likely to linger on a car lot.

People, he said, were “seeking joy.”