This post was originally published on this site

Forecasts for Friday’s jobs report show that we may be experiencing a long-awaited post-pandemic rebound in employment. The economy is expected to add more than 500,000 new jobs. But these big topline numbers obscure the fact that the economic recovery is not reaching everyone. Disabled workers, especially disabled women, were hit harder by the pandemic than nondisabled workers and their return to work has been fragile.

Now hiring: U.S. seen adding 700,000 jobs in June

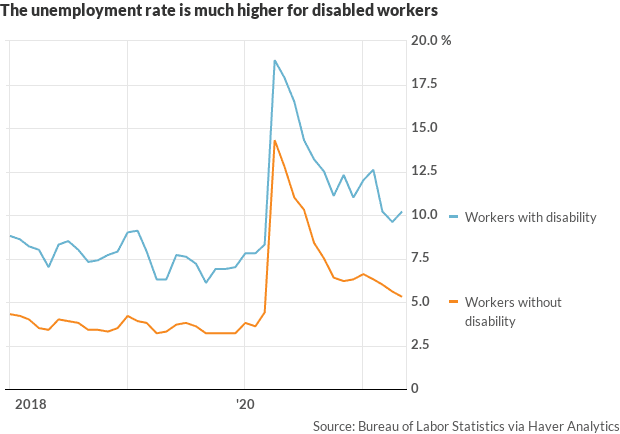

At the height of the pandemic, disabled workers’ unemployment rate reached 18.9% compared with 14.3% of nondisabled workers. And while the unemployment rates for both groups have dropped, the gap between disabled and nondisabled workers has widened. Last month’s jobs report showed that the unemployment rate for disabled workers was still 10.2%, nearly twice that of their nondisabled counterparts, at 5.3%.

One in four adults are disabled, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, so it is impossible to achieve true economic recovery without implementing disability-forward employment policies to protect these workers.

Greater challenges

Because they disproportionately work in the largely in-person service sector, which was particularly hard hit by the pandemic, disabled workers have faced greater health and economic challenges over the last 16 months than the workforce at large. Disabled workers were more likely than their nondisabled peers to be employed in “essential” professions that kept our country functioning during lockdown including, food, agricultural and transportation.

A University of California study showed that in California these sectors experienced a significantly higher mortality rate than other sectors. These mortality rates increased particularly for workers of color. With essential service workers in precarious environments, disproportionately at higher viral risk, it is no wonder that disabled people are being forced out of work. Disabled people were more likely than their nondisabled peers to be unemployed and more likely to be out of the labor force altogether.

But now that the pandemic is receding, disabled workers are facing a new set of challenges. The return to in-person work at many workplaces marks an incredibly critical juncture for the future of the disabled workforce.

Overall, disabled people have long been more likely to be part-time workers, and the pandemic brought a significant increase in disabled people involuntarily having to work part time in 2020. Part-time work can sometimes lead to more work flexibility, which is extremely important to many disabled workers, particularly for parents and workers with lowered immune systems. But the work often leads to a loss in employee benefits, unstable schedules, and sometimes unsafe work environments.

Safety standards lag

The federal and state governments have an important role to play in ensuring that disabled workers can safely do their jobs. The Labor Department’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has been hesitant in creating mandatory safety standards for returning workers, leaving disabled workers with lowered immune systems particularly vulnerable.

A few states are beginning to make to create specific regulations to address this, but many across the country remain unprotected. The Biden administration signed an executive order directing the agency to create an enforcement program to cover “most at-risk workplaces” and directed OSHA to consider releasing an emergency temporary standard (ETS). OSHA released a COVID-19 health-care ETS, which excludes millions of other essential-service workers. This leaves businesses to regulate themselves despite the fact that they have poor track records in doing so.

Long haulers

The return to in-person office work is also happening as more people than ever have become disabled. Researchers estimate at least one in 10 COVID survivors reported at least one symptom that affected their daily living at least eight months after recovery. Symptoms of long-haul COVID can include exhaustion, post-exercise tiredness, and cognitive dysfunction. A recent study showed survivors experienced a loss of hours, jobs, and the ability to work. Forty-five percent of long haulers needed to alter their work schedule and 22.3% stated they couldn’t work as a result of their illness.

COVID long haulers, along with individuals with lowered immune systems, will likely need additional services and accommodations to return to work. Because many of these workers are newly disabled, they may not be aware that they are eligible for accommodations.

A significant outreach campaign to long-haul COVID recipients by federal, state, and local governments, in partnership with worker-rights organizations and businesses can help ensure workers are educated on their protections as disabled workers based on Title I of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Employers can provide clear pathways to requesting accommodations that allow for greater workplace flexibility that include schedule adjustments, work from home allowances, and other accommodations.

Vocational rehab

Resources such as vocational rehabilitation, a federally funded state-run program, are great options for newly disabled workers. It provides counseling and financial assistance for training. But these services don’t always reach the people they need. Vocational rehabilitation has been plagued with high turnover rates and high caseloads.

In 2014, Congress passed the Workforce Innovations and Opportunity Act mandating disabled people receive services within 90 days of being made eligible. A year later, it was found that one third of cases extended past that timeline. States are required to provide 21.3% of the total funds to match federal grants. Yet, like the governors pulling states out of pandemic unemployment assistance funding, states are underfunding their vocational rehabilitation programs, leaving significant pots of federal funds on the table unused.

States and the federal government need to evaluate and update the program to ensure access for disabled people, including long-haul COVID survivors, and guarantee that services match our new post-COVID reality.

The United States has been given an opportunity to re-evaluate what the new norm will be around employment environments and it is up to the government and employers to listen to the needs of their employees. Making substantial changes to how workplaces operate, such as providing greater flexibility and regulatory protections, would help ensure all employees, including disabled workers, are able to obtain and maintain substantial employment, obtain higher wages, and help to boost the economy.

Mia Ives-Rublee is a longtime disability advocate and director of the Disability Justice Initiative at the Center for American Progress.