This post was originally published on this site

No villain in the modern era takes more of the blame for the destruction of the golden past and the ushering in of the miserable present than globalization and its reliable henchman, deindustrialization. From unemployed conservative workers in the American “Rust Belt” to left-wing rioters in the world’s major cities, activists and protesters blame their alienation from liberal democracy on globalization and the elites who disproportionately profit from it.

It’s a tale, as it has often been in the past, of the lotus-eating elites destroying the honest and authentic life of the hard-working commoners. It’s a hell of a story, and as criticism of policies, it is rooted in the reality of actual human suffering. But as a criticism of liberal democracy, it is not new and it is not true.

It’s also a story often pushed by political entrepreneurs for their own gain.

By 2012, for example, just a few years after the global financial crisis and the Great Recession of 2008, 40% of Americans cited the economy as their top concern, and populists of both right and left plowed ahead with charges that democracy was no longer up to the task of providing a stable life for its own citizens.

The political window of resentment over trade and globalization, however, did not remain open for long. Five years later, in 2017, that same number dropped to 10%. As the Brookings Institution scholar Shadi Hamid observed, this forced populists to move their arguments from economics to cultural grievances. “If there were a tagline for today’s populist moment,” he wrote in 2018, borrowing a line from Bill Clinton’s 1992 internal campaign memos, “it would probably be something like ‘It’s not the economy, stupid.’”

This is not to say that fears of economic change are baseless. But the collapse of the American economy predicted back at the turn of the new century by some of democracy’s more dire critics did not happen.

The Great Recession was not forever; it wasn’t even that long of a recession. In fact, the economic death spiral wasn’t even happening while people thought it was happening. New data shows that the 2010s were better for American incomes than the 1990s, suggesting that the American economic situation— even after China joined the World Trade Organization, the so-called “China shock” – was always more stable than its critics asserted.

In retrospect, governing elites of the 1990s and 2000s should have been both more prescient and more candid. These elites in the U.S. and Europe oversold the benefits and downplayed the costs of accelerating the move to a globalized economy; whether they did so out of incompetence or dishonesty, it is always in the best interests of national leaders to say the part about “winners” loudly and then to mumble the part about “losers.”

Perhaps they and the experts who serve them should have been less optimistic, and without doubt they should have made more provisions and strengthened social safety nets to cushion the blow.

If some of these painful outcomes must be assigned to the elites as failures to anticipate the effects of tectonic economic shifts, however, we must also make room here for the behavior of actual consumers.

The ordinary citizens of the American and European economies are conspicuously absent from the economy-driven narratives of democratic failure. There is good reason for this: those ordinary citizens are also voters. Just as no national leader wants to admit the possibility that in a competitive economy some will suffer while others gain, it is political suicide to talk about the choices of the electorate itself.

But in a democracy, the people rule, and to forget what the people actually wanted is to absolve them— and ourselves— of any responsibility for the policies that now are presented by the critics of liberal democracy as evidence of the terminal incompetence of the governing classes.

It is difficult, for example, to confront the challenge of cheap overseas manufacturing without noting how much Americans truly love cheap overseas manufacturing. To stand in a “big box” appliance store on the great shopping splurge after Thanksgiving is to be reminded that Americans buy products made in China and other nations with low labor costs (and products made of cheap components from overseas, as well) at astonishingly low prices and in huge quantities.

This is why the average American home has between two and three televisions in it, before counting the multiple screens of computers or phones.

This is how even Americans of limited means can amuse themselves with hundreds of millions of game consoles.

This is why air conditioners— once an expensive luxury— are now common items sold in local hardware stores for less than the cost of a reasonable family dinner at a restaurant.

This is why people who once could go to work all day without hearing from friends and family now cannot stand idle in a grocery checkout line without texting or playing games. (I am one of those people.)

Oxford University Press

And if the elites have learned little from the experiences of the past 20 years, consumers seem to have learned even less. Americans, for their part, have gone right back to their self-destructive habits of spending and consumer debt. Defaults on car loans, to take but one example, began climbing just a decade after the Great Recession, not because of unemployment, but because Americans keep upgrading their cars.

The problem in all this for supporters of liberal democracy is that complexity doesn’t sell, and it doesn’t move votes nearly as well as rage and resentment. “Global changes create difficult challenges” isn’t much of a slogan for popular mobilization. “Think about the connection between your high living standard and the costs it might carry for other parts of your economy” is a clear loser. And “maybe you shouldn’t be buying three televisions just because they’re cheap” is box-office poison.

Meanwhile, partisans of the nativist right or the revolutionary left diligently trace every moment of pain to a guilty party who can be defeated on the field of political battle: capitalists, the Chinese, bankers, Silicon Valley, bureaucratic mandarins.

It does no good, as a political matter, to respond to such attacks by noting that the real enemy of the blue-collar working man or woman is technology, or that most of the losses in the manufacturing sector over the past few decades were due to improvements in efficiency rather than to cheap foreign labor.

Millions of people have already allowed themselves to become convinced that they had no part in the creation of the modern world. Awash in easy calories and cheap distractions, these citizens in the advanced postindustrial democracies nonetheless believe that they are living in misery.

Tell today’s citizens of the democracies that their parents and grandparents had many of their same anxieties and the answer is always the same: Yes, but this time it’s different. And someone is to blame.

That someone, of course, is never the voters, and until the citizens of the democracies take a hard look in the mirror, they will continue to fall prey to populists who will gladly lead them in a fruitless – and increasingly violent – search for scapegoats while dismantling the achievements of more than two centuries of democracy and freedom.

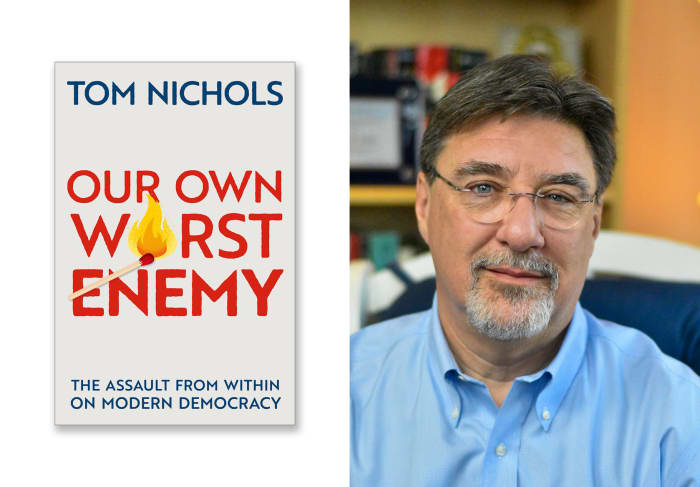

Tom Nichols is a professor and writer who lives in Rhode Island. This article is adapted from his new book “Our Own Worst Enemy: The Assault from Within on Modern Democracy“.