This post was originally published on this site

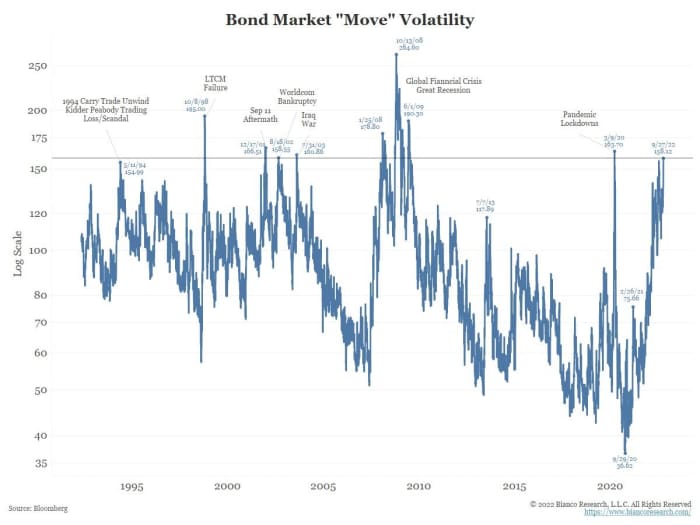

Volatility in the ordinarily sedate world of bonds climbed further on Wednesday to one of the highest levels since the 2007-2009 financial crisis and recession.

The ICE BofA MOVE Index, which tracks fixed-income volatility, rose to 158.99 on Wednesday, according to Refinitiv. That’s up from 158.12 on Tuesday — the highest reading since 2009, with the exception of a brief spike to 163.70 on March 9, 2020, during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Jim Bianco, president of Bianco Research.

Source: Bloomberg, Bianco Research

Wednesday’s action in the MOVE index was accompanied by a dramatic rally in government bonds, after the Bank of England took emergency steps to arrest disorderly conditions in the U.K. market. The rally pushed the yield on the 10-year gilt BX:TMBMKGB-10Y, the U.K. counterpart to Treasurys, down by 50 basis points to 4.014% as policy makers pledged to buy bonds at “whatever scale is necessary” to calm markets. Meanwhile, 2-, 10-, and 30-year Treasury yields posted their biggest one-day drops in years as buyers jumped back into U.S. bonds.

The pullback in yields was credited with lifting U.S. stocks, which were seen as deeply oversold coming into Wednesday’s session after a six-day losing streak that sank the S&P 500 SPX and Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA to levels last seen in November 2020. The Dow finished up by 548.75 points, or 1.9%, while the S&P 500 gained 2%.

In the days prior to the Bank of England’s announcement, U.S. and U.K. bonds had been aggressively selling off. One big reason was the market’s adverse reaction to what investors deemed as a dangerously profligate, tax-cutting budget plan by new U.K. finance minister Kwasi Kwarteng. The other reason was expectations of further interest-rate hikes by many central banks to curb inflation.

“Clearly, the U.K. bond market was getting disorderly and you don’t do limited quantitative easing — when inflation is running as high as it is — unless something is in the process of breaking. To me, it’s the U.K. bond market that is one of the things that’s breaking,” said Mark Heppenstall, chief investment officer of Penn Mutual Asset Management, which manages more than $31 billion from Horsham, Pa.