This post was originally published on this site

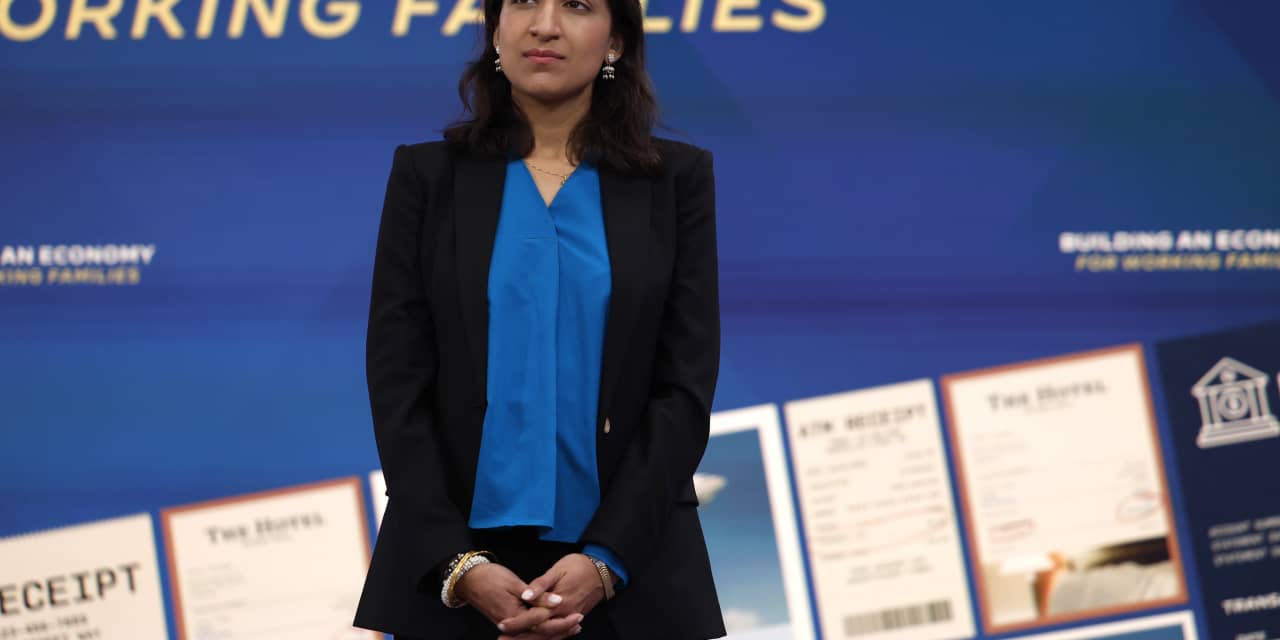

When she was sworn in as chair of the Federal Trade Commission in mid-2021, Lina Khan was hailed as the antitrust sheriff who would rein in Big Tech.

More than 18 months later, critics say the respected academic has been ineffectual so far in the rough-and-tumble world of politics and big business. Tagged with all-but-impossible expectations and saddled with musty antitrust laws that hinder her ability to prosecute tech’s biggest players, Khan finds herself and the FTC at a problematic crossroads, a handful of antitrust experts told MarketWatch.

Khan has so far not shown the political savvy or the organizational skill to be able to crack down on Big Tech, as the Biden administration has vowed to do — but not all of that is her fault, many observers say.

“Five years out of law school and they’re trying to turn her into a savior,” said Larry Downes, co-author of a recent Harvard Business Review piece on the new era of antitrust litigation.

“She came into the job with basically no experience in running a large organization and litigating cases. It wasn’t fair. The decision to name her as chair before becoming a commissioner was a nod to the progressive wing of the party,” Downes told MarketWatch.

From 2021: New FTC chair Lina Khan is Big Tech’s biggest nightmare

White House and FTC officials bristle at any suggestion that Khan has failed in her task so far. They insist she is working to shake up an agency that many have derided as moribund for years and say she has a long list of accomplishments.

“Chair Khan has been an excellent leader of the Federal Trade Commission, and her work promoting competition, cracking down on junk fees and moving to ban noncompete clauses has benefited American workers, consumers and small businesses,” Bharat Ramamurti, deputy director of the National Economic Council, told MarketWatch via email.

The Meta case: When is a loss a win?

So far, however, the results where Big Tech is involved have been less than earthshaking. The most conspicuous setback occurred Feb. 24, when the FTC dropped its opposition, on anticompetitive grounds, to Facebook parent Meta Platforms Inc.’s

META,

purchase of virtual-reality startup Within Unlimited. A federal judge denied the FTC’s bid to issue a temporary restraining order, all but sinking a case many legal experts said lacked evidentiary heft.

“The FTC is dependent on credibility, like any agency. The more cases you lose, the harder it is to maintain credibility with the courts and the public, and [you] lose political capital,” Morten Skroejer, senior director for technology competition policy at the Software & Information Industry Association, told MarketWatch.

“She has politicized a professional, quasi-independent organization,” said Rob Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a nonpartisan think tank. In 2020, Atkinson was the chair of the emerging-technologies policy advisory group for then-presidential candidate Joe Biden. “[The FTC] has become an arm of the White House,” he told MarketWatch.

Compounding the Meta failure was the fact that Khan broke routine agency precedent to take on the company’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, ignoring staff recommendations and opting to sue Meta last year despite the flimsiness of the case against the company, according to two people close to the agency. Statements Khan made before joining the FTC, in which she asserted that Meta should be blocked from making any future acquisitions, further inflamed tensions.

The FTC, along with some legal observers, insists the agency won despite the loss in court. U.S. District Judge Edward Davila’s decision did recognize the agency’s position that mergers could be blocked even if they don’t immediately hurt competition but have the potential to do so in the future.

“The judge sided with the FTC on basically every question of law and laid out a very clear opinion that said the way we were interpreting the law was correct,” Rebecca Kelly Slaughter, a Democratic commissioner, said of Davila’s decision.

Davila agreed that mergers between companies that don’t currently compete against each other still can violate Section 7 of the Clayton Act, which bars deals “whenever the effect would substantially lessen competition and tend to create a monopoly.”

But several days before the ruling, in a rare public rebuke, FTC Commissioner Christine Wilson announced she was resigning in a withering op-ed piece in The Wall Street Journal, saying she had “concerns about the honesty and integrity of Ms. Khan and her senior FTC leadership.”

Wilson pointed to the annual Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey, writing: “In 2020, the last year under Trump appointees, 87% of surveyed FTC employees agreed that senior agency officials maintain high standards of honesty and integrity. Today that share stands at 49%.”

External obstacles and self-inflicted wounds

Khan’s goal of transforming the FTC into a modern-day enforcer of antitrust law has been hindered by a lack of significant federal laws and a dearth of staff, resources and technical expertise, according to Downes and others.

“There have been no serious changes to competition law in years,” Downes said. “Congress has repeatedly failed to update antitrust law.”

Antitrust legislation has been a tough sell given its esoteric nature — and because of the impact technology has had on making life more convenient, Downes said. “Consumers are annoyed and frustrated by Big Tech, but it is very hard to argue with free services,” he said. “It’s hard to argue that free services are harming them.”

But the start of Khan’s tenure was also marked by some self-inflicted wounds.

“Khan made a number of mistakes when she took over as chair,” said Daniel Kaufman, who ended a 23-year career at the agency in October, serving most recently as acting director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection. “She did not engage with staff, and she appointed people to key positions who worked with Commissioner [Rohit] Chopra, whom she interned for. Most new FTC chairs appoint people from the outside.”

But fundamentally, Kaufman told MarketWatch, “there is an enormous disconnect between expectations of what she can achieve and what the law allows her to do.”

Read more: Biden made big promises on antitrust but Lina Khan’s FTC is underachieving, critics say

Those who know Khan say she is meeting resistance because she is trying to shake the long-dormant FTC out of its decadeslong slumber.

“She is reviving an authority that the FTC has not used for years,” said K. Sabeel Rahman, a professor at Brooklyn Law School and a former senior counselor in the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs who has known and worked with Khan for seven years. “The age [and] experience thing is a red herring.”

The ‘hipster antitrust’ movement

On her appointment to the FTC as chair — which surprised some observers who expected her to be named a commissioner — Khan was ushered in with sky-high expectations. She is highly regarded for her academic work, and as one of Silicon Valley’s chief critics, she is considered the leader of the “hipster antitrust” movement among young scholars.

She was also part of a wave of antitrust-touting progressive policy-wonk hires such as Jonathan Kanter, another relative newcomer to the federal government who is now head of the Justice Department’s antitrust division; legal scholar Tim Wu, who served as special assistant to the president for technology and competition policy; and Gigi Sohn, who has been nominated by Biden to the Federal Communications Commission.

Wu was a driving force in crafting a sweeping executive order in 2021 designed to crack down on anticompetitive business practices in Big Tech, labor and other industries. The Justice Department brought an ad-tech antitrust case against Alphabet Inc.’s

GOOGL,

GOOG,

Google this year and is moving closer to an action against Apple Inc.

AAPL,

for its dominant app store. Khan, her detractors contend, has not accomplished anything of similar consequence in regard to Big Tech.

The White House and Khan’s proponents, however, point to a list of her achievements as FTC chair, including suing to block Microsoft Corp.’s

MSFT,

$69 billion bid to buy Activision Blizzard Inc.

ATVI,

which would be the biggest tech acquisition ever; the first significant revision of merger guidelines since the 1970s; a proposed near-complete ban on noncompete agreements for employees; success in securing funding from Congress to raise the FTC’s annual budget by $55 million, to $430 million; and enforcement of “the right to repair,” new rules prohibiting companies from deceiving customers by selling products that cannot be repaired without destroying the device, or that cannot be repaired outside of the company’s own service network.

“Chair Khan has energized the FTC, winning challenges to a $40 billion merger in the semiconductor industry and preventing further consolidation in the lifesaving kidney-dialysis market,” FTC spokesperson Douglas Farrar told MarketWatch, referring to Nvidia Corp.’s

NVDA,

unsuccessful bid to acquire chip designer Arm Ltd. from SoftBank Group Corp.

9984,

and to a new requirement for DaVita Inc.

DVA,

to receive preapproval for anticompetitive mergers. “Beyond merger-challenge victories, she has proposed rules that will free employees and entrepreneurs from illegal noncompete clauses and protect American’s digital privacy.

“The job of the FTC chair is not to make partisan detractors happy, but to do what Congress has mandated: protect American consumers and businesses from unfair methods of competition,” Farrar added. “That’s exactly what Lina Khan is doing.”

Despite the departure of two commissioners — Wilson and Noah Joshua Phillips, who left last year but did not give a reason — and the announced retirement of Holly Vedova, the FTC’s top competition official, after more than 30 years with the agency, Khan continues to have plenty of support from members of both parties, running the gamut from progressives and moderates to conservatives.

An ambitious course that could take years

For now, the agency is charting an ambitious course that could pay dividends for all companies in tech, regardless of their size and stature. But that could still be a long way away, say tech executives.

“I agree with the [FTC’s] philosophy [toward Big Tech], but it has not helped me so far,” Muddu Sudhakar, a serial entrepreneur who is now CEO of software startup Aisera, told MarketWatch. “It is important small guys are protected and innovation is protected. But I don’t want too much regulation. Let capitalism be capitalism.”

Downes finds a “certain genius” in the FTC bringing cases to court that are designed to make a legal point above all else, even above victory — like the case against Meta. “That puts pressure on Congress to effect change, and tech companies to make concessions,” he said.

Katherine Van Dyck, senior legal counsel at the nonprofit American Economic Liberties Project, told MarketWatch that “the agency is sending a message that these mergers aren’t going to be rubber-stamped anymore. A lot of bad case law over the last 40 years is a big ship to turn around.”

Where it all leads is anyone’s guess. Some speculate Khan will forge ahead despite her vocal detractors and oversee a lawsuit against Amazon.com Inc.

AMZN,

before eventually returning to academia.

“The difficulty is that antimonopoly and antitrust law has been conventional for so long. It needs to be updated,” Rahman told MarketWatch. “The FTC’s success will be largely determined over the next five to 10 years if laws move in the right direction.”