This post was originally published on this site

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org.

Lew Ziska was a freshman in college when he realized he had a bigger problem than he thought with his seasonal allergies. “I couldn’t breathe,” recalls the 65-year-old college professor. “It was spring. I could not breathe. Having a 600-pound gorilla sitting on your chest is not a joke. You feel like you’re going to die.”

It wasn’t until Ziska received emergency treatment at the campus dispensary that he regained his breath. “Suddenly, I could breathe again, and everything was fine – but I didn’t have an inhaler then.”

Ziska now knows the “gorilla” was a severe asthma attack triggered by spring allergies. He’s one of the tens of millions of Americans — including one in four adults — who suffer from seasonal allergies.

It might seem ironic (or fitting) that he went on to become a plant physiologist at Columbia University, where he now studies the link between climate change and allergies. Unfortunately, however, the news from the research front is not good.

A March report from Princeton-based Climate Central calls the rise in outdoor allergies a “significant threat to human health.”

A longer sneezing season

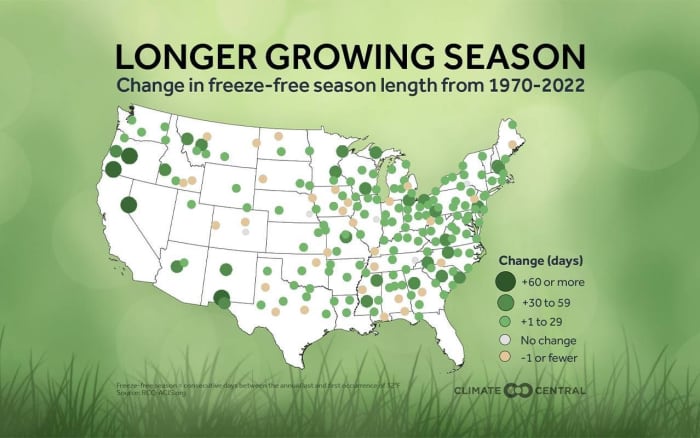

The report affirms, “A growing body of research shows that warming temperatures, shifting seasonal patterns and more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere — all linked to climate change and greenhouse gas emissions — are affecting the length and intensity of allergy season in the U.S.”

“What we’re seeing consistently across North America is that those spring frosts are ending earlier,” says Ziska. “What that’s doing is expanding the time in which pollen is present in the atmosphere — trees in the spring, grasses and weeds in the summer and ragweed in the fall.”

Ziska says spring allergies are seeing the most significant spike. “Trees are primed to start producing pollen and flowering early in the spring when the weather reaches a certain point – that is when there’s no longer a frost. And so when that happens, often they release all their pollen, not in dribs and drabs, but in huge buckets.”

While the news is bad for allergy sufferers “across the board,” the climate impacts could pose a greater risk to older adults. “For the older population, if you suffer from COPD or if you have other respiratory ailments, I think this is something that could exacerbate conditions that are already pre-existing,” Ziska says.

You might like: Want to live longer and healthier? Start looking on the bright side of life.

Multiple threats

There are several climate connections to worsening outdoor allergies. Apart from the longer growing season, the higher concentrations of carbon dioxide in the air from burning fossil fuels act like a steroid for pollen production.

Poison ivy is a particular beneficiary, not only getting a growth spurt from the extra CO2 but producing a more potent form of urushiol. This toxic oil makes poison ivy, well, poison.

Even thunderstorms, also expected to increase in some areas, can exacerbate allergies. Though Ziska says the exact mechanism needs more study, the pressure dynamics around thunderstorms tend to mince up pollen particles and whip them into a frenzy.

“So now instead of breathing in one pollen grain, you’re breathing in lots and lots more little pollen grains, all of which have the ability to affect your immune system,” explains Ziska.

A longer growing season expands the time that pollen is in the air.

Climate Central

The Climate Central report points to a phenomenon called “thunderstorm asthma.” The report explains, “studies have shown high pollen and mold counts around thunderstorms correlate with increased asthma symptoms and hospital admissions.”

Where you live matters

Earlier this spring, the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America mapped the worst places in the nation for allergy sufferers. Perhaps not surprisingly, several cities in Florida – still among the most popular retirement destinations – made the foundation’s Hall of Phlegm (my phrase, not theirs).

But the hot spots were well dispersed, with several in the Midwest. For example, Wichita, Kansas clocked in at number one. So it stands to reason that as the growing season expands in these mid-latitudes, conditions for allergy sufferers will only worsen.

A 2020 study co-authored by Ziska tracked pollen data from 60 stations over a nearly 30-year period and found the biggest spikes had occurred at stations clustered in Texas and the plains states.

These shifts are not just projections based on mathematical models; they’re already happening and at least partially driven by the burning of fossil fuels and emissions of other greenhouse gases.

Overall, the authors determined that “human forcing of the climate system has substantially exacerbated North American pollen seasons.”

Have some honey, honey

This all adds up to a field day for antihistamine makers, but some folk remedies may be worth trying.

It’s long been thought that eating locally-produced raw honey will help alleviate plant allergies because the pollen contained in the honey — gathered from some of the offending plants — helps build immunity to them. But unfortunately, there’s a dearth of peer-reviewed research into the claim.

Richard Ronconi, 85, has been keeping bees for over 50 years. He currently has about 26 hives on his property in Berne, New York. He says, “There are people who swear by my honey and say it really helps them with their allergies.”

“I have no way of validating that,” he admits. “But if you’re allergic to goldenrod, if the bees bring back nectar from the goldenrod plant, it’s gonna have some goldenrod pollen in it.”

While Ziska agrees that makes intuitive sense, “There’s an obvious need to do serious work into this,” he cautions.

“You know, it doesn’t really matter, if it makes you feel better,” notes Ronconi. “Whether it works chemically or just in your head, as long as you feel better, then it’s good.”

Plants and a changing climate

The most recent report from the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change paints a sobering picture of progress thus far toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions that are heating the planet and spinning off effects such as the increasing assault from allergens.

Read next: Paper or plastic? Instead ask which companies are innovating recycling

Unfortunately, few people read these reports, and day-to-day concerns about pandemics, inflation and making ends meet tend to overshadow the stark warnings from scientists. Ziska says how plants of all types react to the changing climate is an under-discussed, but no less important, part of the climate emergency.

“I think that what you can do to get people to care is talk about how specifically climate change is going to affect their health,” says Ziska, “from their respiratory health to the nutrition of the foods that they consume to the quality of the medicines. Because plants are also a source of medicines.”

Craig Miller is a veteran journalist based in the northern Catskills of New York. His reporting is focused on climate science and policy, energy and the environment. In 2008 Miller launched and edited the award-winning Climate Watch multimedia initiative for KQED in San Francisco, where he remained a science editor until August of 2019. He’s also a proud member of his local volunteer fire department.

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org, ©2023 Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. All rights reserved.

More from Next Avenue: